France was in danger and the Revolution was in peril. The Committee of Public Safety had just been created. The Reign of Terror had begun.

Marat, Robespierre's friend, a deputy to the Convention, and editor-in-chief of

L'Ami du Peuple, was a fiery orator; he was also a violent man, quick to take offense. Some saw him as an intransigent patriot; for others he was merely a hateful demagogue.

On July 13, 1793, a young Royalist from Caen, Charlotte Corday, managed,

by a clever subterfuge, to gain entry into his apartment. When Marat agreed to receive her, she stabbed him in his bathtub, where he was wont to sit hour after hour treating the disfiguring skin disease from which he suffered.

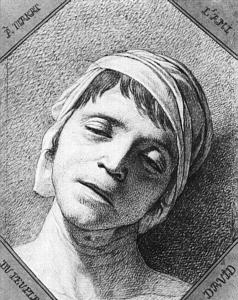

David, who had been Marat's colleague in the Convention, saw in him a model of antique "virtue." The day after the murder, David was invited by the Convention to make arrangements for the funeral ceremony, and to paint Marat's portrait. He accepted with enthusiasm, but the decomposed state of the body made a true-to-life representation of the victim impossible. This circumstance, coupled with David's own emotional state, resulted in the·creation of this idealized image.

Marat is dying: his eyelids droop, his head weighs heavily on his shoulder, his

right arm slides to the ground. His body, as painted by David, is that of a healthy man, still young. The scene inevitably calls to mind a rendering of the "Descent from the Cross." The face is marked by suffering, but is also gentle and suffused by a growing peacefulness as the pangs of death loosen their grip.

David has surrounded Marat with a number of details borrowed from his subject's world- the green covering, white sheet, and wooden packing case, and he has also added a few others, including the knife and Charlotte Corday's petition, attempting to suggest through these objects both the victim's simplicity and grandeur, and the perfidy of the assassin.

The petition ("My great unhappiness gives me a right to your kindness"), the assignat Marat was preparing for some poor unfortunate ("you will give this assignat to that mother of five children whose husband died in the defense of his country"), the makeshift writing-table and the mended sheet are the means by which David discreetly bears witness to his admiration and indignation.

The face, the body, and the objects are suffused with a clear light, which is softer as it falls on the victim's features and harsher as it illuminates the assassin's petition. David leaves the rest of his model in shadow. In this sober and subtle interplay of elements can be seen, in perfect harmony with the drawing, the blend of compassion and outrage David felt at the sight of the victim.

The painting was immediately the object of extravagant praise, then, returned by the Convention to David in 1795, it was rescued from obscurity only after his death. Misunderstood by the Romantics, who saw in it only a cold classicism, it was restored to a place of honor by Baudelaire, who wrote: "This is the bread of the strong and the triumph of spiritualism; as cruel as nature, this painting is redolent of the Ideal. What then was that ugliness which Holy Death so quickly erased with the tips of her wings! Marat can henceforth defy Apollo, Death has kissed him with her loving lips and he rests in the tranquillity of his metamorphosis. There is, in this work, something at once tender and poignant; in the cold air of this room, on these cold walls, around this cold and funereal bathtub, a soul flutters...."

Study of the head for: "The Death of Marat", pen and ink on white paper pasted on brown paper, Musée National du Château de Versailles.

|

Return to the J. L. David page